The origin, development and importance of Hero-stones in India – special lecture by Dr Poongundran organized by the Indological Research Institute (IRI) (3)

Discussion on the Special lecture: After the lecture, there was a discussion also and many asked questions and he answered and explained nicely. There were some PhD students, who asked specific questions and he replied. Thus, the discussion was live and enjoyable. Generally, in other meetings such free discussion is not allowed, but, here, all could get clarification from the speaker. Definitely, the session set an example for academic proceeding and healthy discussion, as it continued for half-an-hour.

- During which rule, the hero-stones were found maximum?

- Considering the places (Dharmapuri, Krishnagiri) and other places of Thondaimandalam, it is believed that during the Pallava period, maximum Hero-stones were erected

- Under the category of “Hero” of Hero-stones, who were there?

- Maximum warriors, soldiers and individuals, rarely King, chieftain or ruler of higher status. Now, interpretation has shifted to “marginalized” and so on.

- Where, the Hero-stones are found maximum?

- According to the historian Upinder Singh, the largest concentration of such memorial stones is found in the Indian state of Karnataka. About two thousand six hundred and fifty hero stones, the earliest in Karnataka is dated to the 5th century CE.

- Why the Kumbam / kalasam like object was depicted, what is its significance?

- It is not Kalasam or Kumbam, as explained above. The one object which requires elucidation is what has been described as a receptacle (Simi, சிமிழ்). The relevance of a Simi = small container, is not clear. It looks more like a pedestal or a representation of what might have been the form of a shrine raised in memory of the dead hero.

- Is there any relation between the script found on the pottery and Hero-stones?

- As for as the script is concerned, it is the same only and the language is Tamil. The script is called Brahmi, Tamil-Brahmi, Tamili and so on.

- When the transformation of nettuzhuttu to vattezhuttu took place?

- During 5th-6th centuries writing transferred to different media and the script also changing from hard surface to soft surface.

- Whether Hero-stones convey any important message?

- Hero-stones serve as memorial stones to the warriors, self-sacrifice, defender of villages etc., and hence they were elevated to the stages of God, Goddess or Protecting deity of the villages, group of people etc.

Development of Hero-stones: Whether megalithic burials led to the Nadukal practice has to be studied carefully. There were five stages in the evolution of the megalithic burials, said Rajan. They were –

(1) megalithic cairn circles,

(2) cairn circles with tall menhirs,

(3) tall menhirs with Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions on them,

(4) short menhirs, about one or two metres tall, with Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions, and

(5) the culmination of shortened menhirs into hero-stones with Tamil Vattelluttu inscriptions of the fifth and sixth century CE. In the last and fifth stages, the menhirs were reduced to hero-stones, each with the engraving of the hero who was killed in a cattle raid. Such hero-stones, during the transformation period of Tamil-Brahmi into Tamil Vattelluttu script, belong to the fourth century CE. They have Tamil Vattelluttu inscriptions, and are found in the Chengam area of present-day Tiruvannamalai district, and in Dharmapuri district[1].

The Sangam literary references and details about the Nadukals: The Sangam period (3rd century BC to 3rd century CE) literature such as Ahananuru and Purananururefers to the hero stones. They were not plain in character. Generally on the hero stones either at the top or bottom details like the name of the hero, the name of the king and the hero met with his death (his heroic exploits and philanthropic deeds) was engraved. The upper portion of the stone hero’s figure was depicted or appeared. They were mostly planted nearer to the irrigation tank or lake or outside the village. These everlasting stones were worshipped. Tolkappiyam, the earliest extant Tamil grammar, speaks of six stages in the ritual economies associated with the erection of hero stones. They were –

(1) katchi i.e. discovery,

(2) kalkol i.e. invitation,

(3) Nirpatai i.e. Bathing of the stones,

(4) Nadukal i.e. Erection,

(5) Perumpadai i.e. offering of food and

(6) valttu i.e. Blessing.

Evolution of Hero-stone: The origin of erecting hero stone or hero worship evolved from the Iron age megalithic burial tradition. There were three distinctive stages in the erection of memorial stones.

1) Megalithic monuments were raised as memorials.

2) The iron age graves were raised.

3) Later graves were abandoned menhir with inscription (memorial stone) was raised. The recent discovery from Pulimankombai, Thathapatti, just a few km from Pulimankomabi (on the southern bank of river Vaigai; Dindigul district) are the earliest best example for short menhirs about one or two metres tall, with Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions. Later the Menhirs were reduced to hero-stones. There was a difference between the memorial stone and hero stone. Memorial stones contained funeral remains but the hero stones were erected to show respect over to a death person without his remains. The Pandyas were one of the three crowned monarch of the Sangam age, ruling the southern part of the present Tamil Nadu State (from 6th century to 16th century CE). They followed this tradition as in the Sangam age.

Nadukal[2]: The given details about Nadukal[3] (literally meaning ‘an erected stone’) show how the practice is evolved into a full-fledged ritual. Initially, the place where the person died is considered as important or sacred and nadukal is erected there[4]. Then, a place is selected for erection[5] followed with other rites –

- covered with cloth;

- stone is placed on an elevated platform;

- washed with good waters;

- name and fame of the dead are inscribed;

- worshipped with the offer of flowers, food, and incense; even animals are sacrificed;

- lamps are lit;

thus the dead is elevated to the status of god and considered as God[6]. The direction was chosen as ‘south’ perhaps coinciding with the direction in which the body fell or found. From this, the concept of fore-fathers living in the southern direction with the status of god might have been developed. In fact, Puram emphasizes that one should perform the duty of offerings to their forefathers, who live in the southern direction, implying the pitrs or departed ancestors[7]. Similarly, a son saves his forefathers of his lineage by his actions. Thus, the offering of panda or rive ball is recognized as an important ritual[8].

Nadukal[9]: For the preparation of Nadukal, six steps have been prescribed:

1. Selection of stone,

2. Chiselling,

3. Immersion in water (for cleaning),

4. Erection (at a place),

5. Engraving and

6. Paying homage (with offerings)[10] .

Surprisingly, very similar rites are followed by Brahmins even today on 10th day for the dead. The ceremony contains the following steps:

- Selection stone,

- Cleaning with water, milk etc.,

- Seating on darpa (Kusa) grass and writing the name of death on it with the grass symbolically,

- Pashana Sthapanam (consecration of stone = stone fixing, one at the house and another on the banks of river or where rituals are conducted)

- Invoking spirit to enter and

- Offerings with Vastodharana (offering of dress) etc.

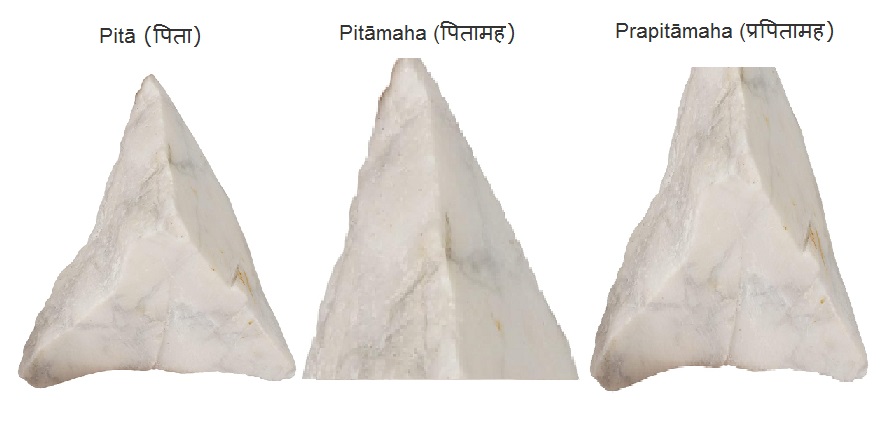

| Pitā (पिता) | Pitāmaha (पितामह) | Prapitāmaha (प्रपितामह) |

| Father | Grand father | Great grand father |

These practices appear similar and therefore, they have to be studied critically, how such practices could have existed in two different cultures, as now some researchers may try to interpret[11].

© K. V. Ramakrishna Rao

05-05-2024

[1] Rajan, K. 2000. South Indian Memorial Stones, Manoo Pathippakam, Thanjavur

[2] K. V. Ramakrishna Rao, Karanams of the Ancient Tamils, The paper was presented at the first session of Tamilnadu History Congress, held at Madras from September 10 and 11, 1994. Accepted for publication, but not published in the Proceedings, because there was no space (as accepted by the organizers)!

[3] Puram. 221, 260, 263, 264, 265, 329, 335.

Agam.35, 53, 67, 131, 179, 269, 289, 297, 298, 365.

Malaipadukadam lines 387-389; Ing. 352 (references about Nadukal).

[4] Puram.260:22-28, 263:7-8, 265:1.

[5] Puram.260:1-4.

[6] As in.Puram, all references about nadukal;

God – Puram. 335:11-12, 265:4-5, 329:1-4; Agam.35:8-11.

[7] Puram.6:4-5, 58:4-5.

[8] Puram.234:2-6, 249:12-14, 360:17-20, 363:10-14.

[9] K. V. Ramakrishna Rao, A Critical Study of Karanams of the Ancient Tamils and the Samskaras, A paper presented at the Swadeshi Indology Conference – 3 “Tamilnadu – the Land of Dharma” held at from to 2017

[10] Tol.Purattinaiyiyal.Sutra.60. Similar steps are found in the Sangam literature as explained.

[11] Under the Aryan-Dravidian dichotomy and the racial interpretation that is favourable to the Dravidologists, these practices could pose chronological challenges.

Filed under: heritage, hero stone, hero-stone, stone, stone-axe factory, students, subject, tamil, Tamil Brahmi, tamil chauvinism, Tamil inscription, Tamil manuscript, Tamil manuscripts, tamil sectarianism, tamil separatism, tamili, tamilnadu, tradition, training, wheel | Tagged: archaeology, europe, hero, hero stone, hero-stone, hero.stone, history, India, memorial, memorial for dead, memorial for death, memorial stone, nadu kal, nadukal, Poongundran, tamil, Tamil Brahmi, tamil chauvinism, Tamil language, travel | Leave a comment »