The origin, development and importance of Memorial-stones in India (4)

Sind / Sindh had been part of India / Bhart for centuries, till Arabs invaded and tried to Islamize……

The warriors of Sindh were resisting them with their valour……

However, they could not match with the cunningness of their enemies, when they were following the code of conduct of war etc…..

In 712, the invasion started, within 300 – 400 years, Sindh was Islamized……

and slowly, all the monuments, temples, sculptures etc., started disappearing, as the iconoclasts were destroying them regularly……

now the condition of Hro-stones are like this…….

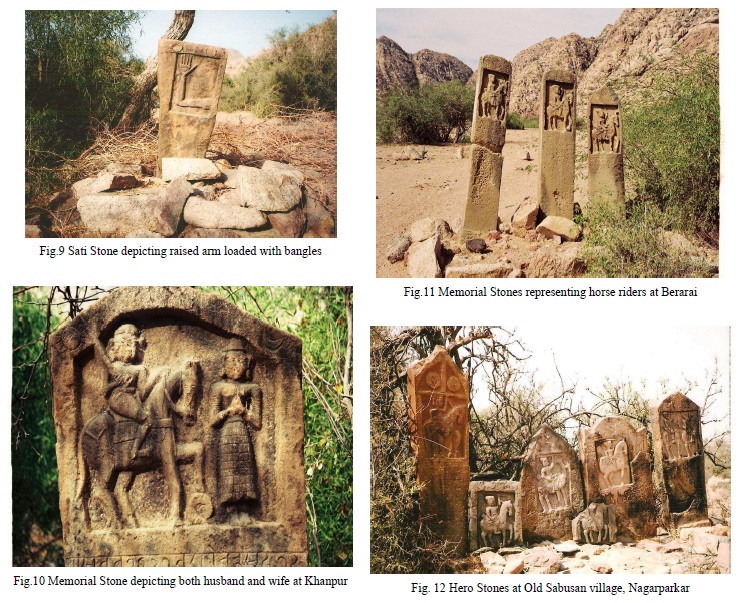

Hero-stones in Sind: Lower Sindh in southern Pakistan is dotted with many ancient cemeteries boasting the tombs of fallen heroes, and stones erected in memory of their heroism and chivalry (Hero stones). Most of the tombstones bear weaponry depictions symbolizing death in the line of action or at least participation in battle. They are found at Oongar in the district of Thatta, province of Sindh and , a Jats burial site, is located fifty kilometres from the city of Hyderabad, close to the Buddhist stupa of Sudheran in the district of Tando Muhammad Khan, also in Sindh[1]. One finds inscriptional slabs lying all over the site at the cemetery of the Jats but it is difficult to find any inscriptions at all at the Oongar necropolis since all of the chaukhandis have disintegrated and not a single tombstone is in its original condition[2]. In other words, they were destroyed and only parts are available there now. Hero-stones and sati stones found in the Sind province of present Pakistan has been pointed out by many and also noted that they are disappearing[3]. Central Asian and Bactrian areas exhibit broken sculptures of many panels and they are identified and interpreted differently. As the Indian kings / people were massacred there, it is mentioned as Hindu-kush = Hindus blood i.e, the Hindus were completely routed and eliminated there, and hence, memorial stones must have been erected. Till “Hindu-kush” occurred incidence at that area, they were there struggling with invading groups. Thus, only left out monuments have been recorded by Auriel Stein during his exploration. After Talibanization, even sculptures in the museums were destroyed and therefore, the fate of the sculptures and paintings found at the sites cannot be imagined.

Memorial stones in Cambodia / Siam / Thailand: In the Siamese culture, schools pointed out about the bloody sacrifice to the Earth Goddess offered at the Door of the Underworld, an ancient tree, a termite mound, a cave, a ring of stones[4]. At the time of the Buddhist ordination ceremony and its site, the Uposatha hall was surrounded by a ring of stones. Michael Wright noted that, “There is no evidence that these stones were developed from anything in India or Lanka, whereas scholars have proposed an affinity with prehistoric circles of rough-hewn stones found in the Northeast.” However, as the South Indian merchant guilds were having close contacts with these areas, there were possibilities that some sailors, merchants and other crew members might have died there and they might have erected memorial stones for them. Stone circles are considered as memorial stones, as noted above. Here, in the Siamese tradition, as there had been mixture of several peoples, the changes noted would be appreciable. Whether such circle stones were used for good or bad purposes – is also difficult to ascertain now. In any case, they were associated with sacrifice / death only.

Interpreting death, last rites and memorial stones in the context of race, language etc., by the colonial and other ideologists: Indians must have had their territory touching the other dominant civilizations like Sumerian, Egyptian, Persian, Greek and Chinese. Thus, their influence on the other cultures has been appreciable. That is why most of the people of the ancient civilizations wanted to come to India. Indologists were pointing out such similarities and facts during last 150-300 years, but, suddenly changed their attitude. Thus, they changed their theory of the origin of race from the Ganges valley to other places[5]. The historiography was also changed accordingly. The glorification of Indian civilization turned to criticizing even disparaging. This attitude could be noted from the works of William Jones also. With the history writing of Vincent Smith, the Indian history was reduced to 2000 years starting with the Alexander’s invasion / Asokan script. About philosophy, initially, the world scholars accepted that India was the origin of philosophy, thus, every book of philosophy started with Indian philosophy. Thus, the fight started between India and Greece and Indian history has been made to start after Alexander’s invasion, the “sheet anchor of” Indian history. Then, “Aryan-Dravidian” race theory was introduced to dive, but the underlying concepts (rites conducted from birth to death) match with each other. However, the comprehensive and holistic study of Hero-stones gives a different picture. Again, one could note the commonality, in spite of the fact that such practices were carried on far and wide and even chronologically varied from Bronze Age to Modern Age.

Conclusion: Only few examples have been given for each area and state for illustrative purposes. An exhaustive study can also be made incorporating all details after conducting field study and reading local literature. Thus, with limited study and the above discussion, the following points are noted as conclusion:

- The belief in soul, transmigration of soul, karma, life after death, rebirth, cycle of birth and death, etc., have been the basis for the creation of the memorial stone.

- Even during the Bronze Age period, Indian Hero-stones were found in the Central Asia, but, portions were destroyed.

- There is difficult in connecting protohistory with historic narratives in the Indian context, as historians have such thumb rule.

- Logically, scientifically and technologically, such restriction appears to be artificial, inconsistent and redundant considering many other archaeological, material and scientific evidences.

- After the Mahabharat War around 3102 BCE, the participant armies with warriors dispersed and started moving to their destination[6]. However, as some could not reach, they settled down on the way and they became new dynasties and people groups. However, many commonalities could be noted among these people groups[7]. Jains – essences, gymnosophists (people wearing no dress or white dress); Rajaputs – Scythians, etc[8].

- The Hero-stones were found in the areas of Central Asia, Gandhara, Sind and other provinces on the west and Burma, Siam, Kedah etc., on the East.

- That Indic / Hindu / Vedic / Sanatana believing people were living in many parts of the world, at a particular time can also be understood and known from the prevalent of memorial stones and related philosophy.

- Thus, the memorial stone erection had been an Indian practice found from the Bronze Age to 18th century.

- The dichotomy of dividing Indians based on race, language etc., is also cleared considering the prevalence of memorial stones in different places as pointed out, as “karma” continues!

© K. V. Ramakrishna Rao

09-05-2024

[1] Kalhoro, Zulfiqar Ali. “Memorial Stones of Sindh, Pakistan: Typology and Iconography.” Puralokbarta 1 (2015): 285-298.

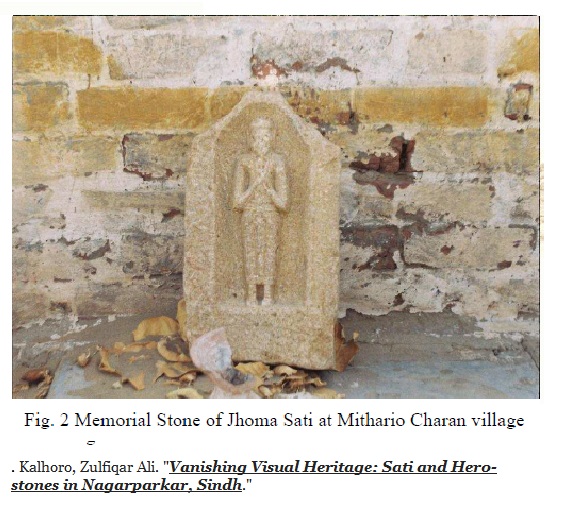

[2] . According to the notables of Oongar, village people have purportedly removed many of the decorative slabs either to sell in the lucrative markets in such items or simply in order to decorate their drawing rooms with these valuable pieces of art. Kalhoro, Zulfiqar Ali. “Vanishing Visual Heritage: Sati and Hero-stones in Nagarparkar, Sindh.” P.54

[3] Kalhoro, Zulfiqar Ali. “Vanishing Visual Heritage: Sati and Hero-stones in Nagarparkar, Sindh.” Journal of Indian Society of Oriental Art 27 (2010): 232-238.

[4] Wright, Michael. “Sacrifice and the underworld: death and fertility in Siamese myth and ritual.” Journal of the Siam Society 78.part 1 (1990).

[5] Léon Poliakov. The Aryan Myth: A History of Racist and Nationalist Ideas in Europe. New York, 1974.

As the European Indologists were using the expression “Aryan,” perhaps, even the Sanskrit scholar like B.G. Tilak was misled and tried to locate the Aryan origin to “Arctic region.”

[6] Even the Greeks were mentioned as “degraded khastriyas,” by old Indologists, but, such details were suppressed later in 20th century itself.

[7] Pococke, Edward. India in Greece; Or, Truth in Mythology... Griffin, 1856.

[8] These are discussed by Richrd Garbe, Col. Tod and others linking Christianity with India, lost tribes etc.

Filed under: academicia, anteshti, anthropology, anti-brahman, anti-brahmin, antique, antiquity, archaeological remains, archaeological sites, Ariyar, artifact, arya, Aryan, astronomy, Balochistan, Brahmi, Brahmi potshred, Brahmi script, broken head, broken parts, broken pillar, Cambodia, ceramics, chalcolithic, culture, Damila, dead, death, Dravidam, dravidar, Dravidi, Dravidian, ethnology, evidence, evolution, hero stone, hero-stone, hindu-kush, maritime, megalith, megalithic, memorial for dead, memorial for death, memorial stone, methodology, neolithic, neolithic cattle keepers, neolithic cattle raiders, paleontology, pottery, race, racialism, racism, rebirth, Sangam, sangam, Sangam literature, script, siam, Sindh, soul, thailand, tomb | Tagged: art, birth, death, hero stone, hero-stone, hero.stone, history, India, life after death, memorial for death, memorial stone, neolithic, neolithic cattle keepers, neolithic cattle raiders, neolithic period, paleolithic, paleontology, politics, soul, stone, stone work, tomb, tomb worship, transmigration of soul, travel | Leave a comment »