Proceedings of the symposium on ‘Art and Culture of Tamil Nadu Reflected Through Excavations’ – held Meenakshi college, on august 29th and 30th 2019 [2]

Dr R. Sivanantham, Deputy Director, TN State Dept of Archaeology, Egmore, Chennai: He led the fourth phase of Kizhadi excavations and now continue with the fifth phase. The first three phases had been conducted by the Archaeological Survey of India, and the fourth and now fifth by the state department. A total of 13,638 artifacts had been unearthed during the first four phases. The excavations that took place in 2014 – 2015, 2016-2016 and 2016-2017 found 7,818 things used by the people of the ancient era, while the fourth phase — between 2017 and 2018 — brought out 5,820 ancient things. About his inviting P. J. Cherian, some controversy was there, because, the Patnam excavations were criticized for the secretive and highly private way of working methodology.

Ms T. Sreelaksmi, Superintendent Archaeologist, ASI, Excavation branch -6, Bengalore – Gottiporlu excavation: She claimed that the site was already excavated, and her group went there to review the condition. The discovery of a 40-acre walled enclosure with artifacts at Gottiprolu near Naidupeta in Nellore district has come as a source of major encouragement for archaeologists and historians, who believe the area was a major maritime trade point in ancient days[1]. The recent findings would help corroborate theories pointing to a historic maritime past. Prominent among the findings are goblet-shaped vessels and conical jars which are worth mentioning as they are supposed to have been used by the elite[2]. These were not used for cooking but were used to consume wine,” surmised Dr. Sreelakshmi, Superintending Archaeologist, Archaeological Survey of India, Excavation Branch VI, Bengaluru. Dr. Sreelakshmi, a student of Prof. K.P. Rao, Department of History, University of Hyderabad (Central University), along with her team, made these discoveries while she was re-visiting the findings of Prof. Rao made during the early 1990s along the Swarnamukhi river[3].

Prof. Rao made his first findings made when he was associated with S.V. University in 1993. “This probably indicates that it is a regional capital which is significant in terms of defence, maritime and economic activity. This place seems to have been culturally significant. We can say that the place must have played a vital role around the 1st and 2nd Century AD. This can be termed as a unique site in terms of archaeological evidence in South India,” he said[4]. The site, with 45 settlements, provides evidence to the theories proposed by experts at Arikamedu, Pondicherry, Sisupalgarh in Odisha and Kaveripatnam in Tamil Nadu where some artifacts related to maritime trade were found. However, Gottiprolu is a much bigger site and proves several literary and historical observations made by noted historians. In fact, this is the first such excavation by the Bengaluru excavation branch in AP. Established in 2001, it carried out excavations at Kurugodu (Karnataka), Keeladi, Kodumanal (Tamil Nadu) where Neolithic settlements and elaborate structural remains of Sangam period were found.

Roman connection: A conical jar placed at the eastern side of the structure is an important find as such jars are widely distributed in Tamil Nadu and are considered to be an imitation of Roman Amphorae jars. A series of broken terracotta pipes fitted into one another found near this structure shed light on the civic amenities maintained by the occupants of this site. The most outstanding discovery so far made at the site is a massive brick structure that rises to a height of nearly 2 m and about 3.40 m in width. The site of Gottiprolu lies on the right bank of a distributary of the Swarnamukhi, 17 km east of Naidupet and 80 km away from Tirupati and Nellore. The archaeological mound is known as ‘Kota Dibba’ (fortified mound).</p>

Dr R. Pongundran, Archaeological officer (Retd), State Archaeology Dept, Egmore, Cennai: He tried to interpret that Velirs could be living in Kizhadi area, as one potsherd reportedly contains the name “oliyan.” He argued that “Oli” and “Veli” are one and the same. He was attempting to argue that the Velirs were part of the ancient Tamizhagam and they never migrated from the north to south. Even, he did not accept the references that the Velirs case down to south, when their forefathers of 49th generation was living at the place of “Tuvarai” viz., Dwaraka. I had discussion with him about the Velirs and connected issues. He argued only with literary evidences, that too, with his forced conclusions. His attempt of equating words found here and there and other comparisons have no logic. His weakness is exposed in his in interpretation of “Veladhan” and “Velaparppan.” Most of his presentation was from his published books [5]in Tamil about “Valirs.”

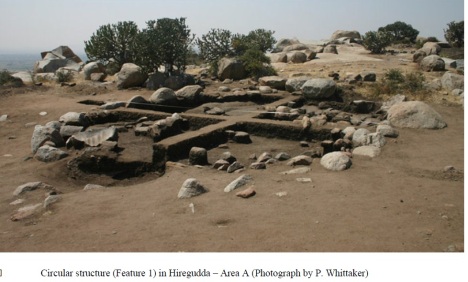

Sanganakallu – Dr Ravi Korisettar, UGC Emeritus Fellow, Karnata University, Dharwad University: Nearly, he took two hours went on narrating about his excavation, but, all materials had already been published 10-15 years back. The later prehistoric settlement history of the mid- southern Deccan, south India, is well preserved in the archaeological sequence at the Sanganakallu-Kapgallu hill complex. The Neolithic to Megalithic remains are scattered between the Sannarachammagudda (Sanganakallu) and Hiregudda (Kapgallu) hills on the Bellary-Moka road, midway between the west bank of the Hagari River and Bellary town in Karnataka. The archaeological sites are referred to as Sanganakallu Neolithic after the largest village in the neighbourhood of the hill complex. The patterns in stone tool technology among Mesolithic, Neolithic and Iron Age localities in the Sanganakallu–Kupgal site complex, Bellary District, Karnataka, South India were studied[6].

Statistical tests are used to compare proportions of raw materials and artefact types, and to compare central tendencies in metric variables taken on flakes and tools. Lithic-related findings support the inference of at least two distinct technological and economic groups at Sanganakallu–Kupgal, a microlith-focused foraging society on the one hand, and on the other, an agricultural society whose lithic technologies centred upon the production of pressure bladelets and dolerite edge-ground axes. Evidence for continuity in lithic technological processes through time may reflect indigenous processes of development, and a degree of continuity from the Mesolithic through to the Neolithic period. Lithic production appears to have become a specialised and spatially segregated activity by the terminal Neolithic and early Iron Age, supporting suggestions for the emergence of an increasingly complex economy and political hierarchy.

Sanganakallu-Kupgal area – stone-axe factory: A 10-30m wide dolerite dyke on the northernmost of the complex of granite hills in the Sanganakallu-Kupgal area became one of the main sources of raw material for the production of stone axes in southern India during the late prehistoric period[7]. At least three large hill settlements (several hectares each) were established in the hill complex, and one of them appears to have gradually developed into a large-scale production centre. Quarrying and axe flaking started around 1900 cal BCE, during the so-called Ashmound phase of occupation, and reached its maximum development between 1400- 1200 cal BCE, when a large region of the south Deccan plateau might have been supplied with finished and half-finished products from Sanganakallu. Systematic archaeological excavation and survey carried out since 1997 in the Sanganakallu-Kupgal area, including the dyke quarry itself, has yielded tens of thousands of production flakes, blanks and macro-lithic tools related to the flaking, pecking and polishing of the axes. The ongoing study of these materials permits us to gain insight into the organisation of production in this area from a temporal and spatial perspective. In view of the social and economic transformations taking place in the Deccan plateau during the second half of the second millennium BC, some key questions concern the relationship between intensification of production and the social division of labour between different working areas and settlements.

© K. V. Ramakrishna Rao

01-09-2019

[1] The Hindu, ASI unearths new evidence of Nellore’s maritime history, Appaji Reddem VIJAYAWADA, MAY 11, 2019 07:39 IST’ UPDATED: MAY 11, 2019 07:39 IST

[2] https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/andhra-pradesh/asi-unearths-new-evidence-of-nellores-maritime-history/article27101219.ece

[3] Deccan Chronicle,

[4] https://www.deccanchronicle.com/nation/current-affairs/190519/historical-findings-hold-key-to-the-future-asi.html

[5] “Tolkudi Velir Vendar” = The Ancient Kings belong to Velir class and “Tolkudi-Velir-Politics (Sengam Nadukals-oru aayvu)” = The Ancient Tribes Velir – Sengam Hero stones, a Study, have been his books published in Tamil.

[6] Shipton, Ceri, et al. Lithic technology and social transformations in the South Indian Neolithic: The evidence from Sanganakallu–Kupgal. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 31.2 (2012): pp.156-173.

[7] Risch, Roberto, et al. The prehistoric axe factory at Sanganakallu-Kupgal (Bellary district), southern India. Stone axe studies III. Oxbow Books, 2011.

Filed under: blade, cutting, flake, Gottiprolu, Kapgallu, mesolithic, paleolithic, R. Pongundran, R. Sivanantham, Ravi Korisettar, Sanganakallu, Sanganakallu-Kapgallu, sharpening, stone-axe factory, T. Sreelaksmi, tool | Tagged: absolute dating, archaeological survey of India, chalcolithic, dating, Gottiprolu, Kapgallu, marine archaeology, megalithic, mesolithic, neolithic, paleaolithic, paleobotanical research, R. Pongundran, R. Sivanantham, Ravi Korisettar, relative dating, rescue archaeology, Sanganakallu, Sanganakallu-Kapgallu, startigraphy, stone-axe factory, stratigrapgical, T. Sreelaksmi | Leave a comment »